What to expect from this blog post

This blog post is meant to be an introduction to PyO3 by walking the reader through the build process of a non-trivial extension module in Rust using PyO3. Some familiarity with Python and Rust is recommended to get the most out of this post, basic understanding of Bitcoin concepts may be required to fully grasp the code samples.

Sample application

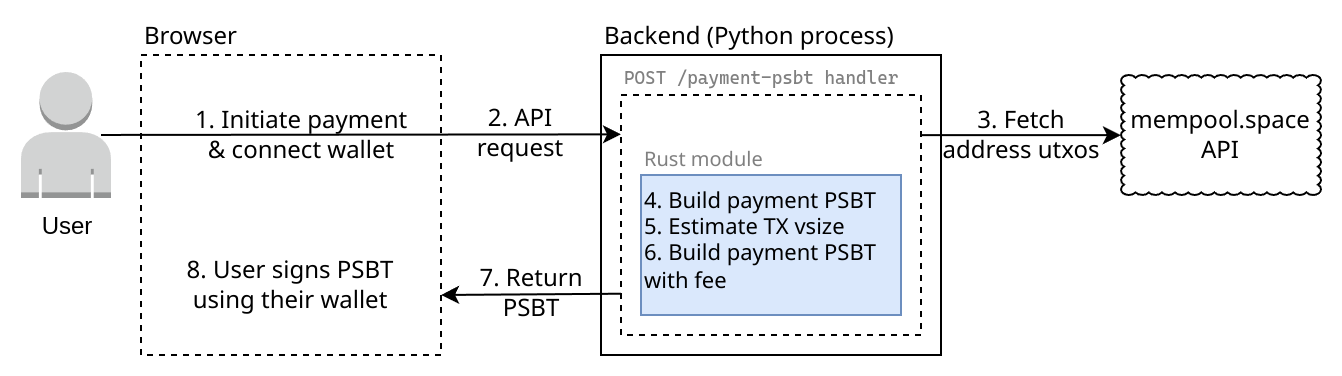

The sample application exposes a simple UI that allows the user to submit a Bitcoin payment by signing (and optionally broadcasting) a Partially Signed Bitcoin Transaction (PSBT) that was built by the application’s backend. The code has been tested in Chrome using the XVerse Wallet extension, by default the application is configured to use Bitcoin’s Testnet3 chain. The application’s code can be split into three components:

- Frontend code that handles user input and wallet interaction, implemented in vanilla Javascript.

- Python backend code that takes care of the inbound HTTP request and the outbound API request to mempool.space.

- Rust code that relies on the

bitcoincrate to build the PSBT.

The following diagram shows how the data flows across said components:

Bootstrapping the extension module

Before we can write a single line of code, we need to figure out a way to build our module, and for that we’ll use Maturin, which is a tool that allows us to build (and publish) Rust-based Python packages. Maturin also includes a useful boilerplate generation sub-command that will create everything we need to compile Rust code into a Python module.

# Generate our module skeleton and creatively name it "btc"

# We passed the --mixed flag because we want a hybrid (Rust & Python) project so we can add type hints later

$ maturin new --bindings pyo3 --mixed btc

# Let's check what was generated

$ tree

.

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── pyproject.toml

├── python

│ ├── btc

│ │ └── __init__.py

│ └── tests

│ └── test_all.py

└── src

└── lib.rs

python -m venv .venv && source .venv/bin/activateWe can see Maturin generated a Rust project with some source samples, since we indicated that we wanted to use PyO3

bindings the pyo3 crate has been included as a dependency, all that is left is to install the bitcoin crate with

cargo add bitcoin@^0.32.0 and replace the content of the btc/src/lib.rs file with the following code sample:

use std::str::FromStr;

use pyo3::{exceptions::PyValueError, prelude::*};

use bitcoin::Address;

// The following comment will go into the function's docstring

/// get_address_type returns the provided address' type as a string

#[pyfunction]

fn get_address_type(address: &str) -> PyResult<String> {

let address =

Address::from_str(address)

.map_err(|_| PyValueError::new_err("invalid address"))?

.assume_checked();

let address_type = address.address_type().map_or("other".to_owned(), |at| at.to_string());

Ok(address_type)

}

/// A Bitcoin helper module implemented in Rust

#[pymodule]

fn btc(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(get_address_type, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}

PyO3 is doing some heavylifting for us, these are some notable examples:

- The

pyfunctionmacro allows us to expose Rust functions to Python. PyResult<T>is an alias forResult<T, PyErr>, a common pattern used across the stdlib and many libraries, if we return theErr(...)variant it will raise an exception in Python, which is what we’re doing when the provided address cannot be parsed.- The

pymodulemacro allows us expose a Python module by declaring a function that will “build” our module by adding our functions, classes and submodules.

In general, implementing a Python extension module is straightforward thanks to PyO3’s types transformations and macros for exposing functions, classes and modules, this allows experienced Rust developers to write idiomatic code by making use of standard Rust types, abstractions and patterns.

Building and testing our code

We have some functional code so let’s give it a quick test by building it and starting a Python interpreter to import and smoke test the module.

# This will build and install our module in our virtualenv

$ maturin develop

🍹 Building a mixed python/rust project

🔗 Found pyo3 bindings

# ... output omitted for brevity ...

🛠 Installed btc-0.1.0

# Now spin up a Python interpreter to execute our new native function

$ python

>>> import btc

>>> btc.get_address_type("bcrt1qg3gmqfdwgteve988hvps7kws2kdzagtkqf6gu0")

'p2wpkh'

>>>

We can even write a simple Python unit test in btc/python/tests/test_all.py:

import btc

def test_get_address_type():

assert btc.get_address_type("bcrt1qg3gmqfdwgteve988hvps7kws2kdzagtkqf6gu0") == "p2wpkh"

or a Rust one in btc/src/lib.rs:

#[cfg(test)]

mod test {

use super::get_address_type;

#[test]

pub fn test_get_address_type() {

assert!(get_address_type("bcrt1qg3gmqfdwgteve988hvps7kws2kdzagtkqf6gu0").unwrap() == "p2wpkh")

}

}

Now that we’re able to build and run our extension module, we’re ready to tackle the actual functionality that we want to build, a PSBT that allows us to charge our user an arbitrary amount of Bitcoin.

Brief introduction to PSBTs

At a very high level, a PSBT is a serialization format that allows a set of actors (i.e. users, services, devices) to build and sign a Bitcoin transaction incrementally. PSBTs are particularly useful when the transaction being built requires UTXOs1 owned by different parties.

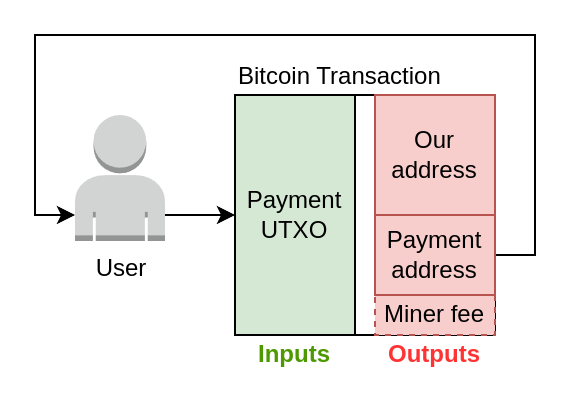

For demostration purposes, we’ll keep our transaction architecture relatively simple. We’ll charge the user a flat fee of 1000 satoshis, for this we’ll select one UTXO with enough sats to cover that amount and the miner fee, the difference will be returned to the user’s payment address. The following diagram portrays our desired transaction:

miner_fee = sum(inputs) - sum(outputs).Building a simple PSBT with Rust

I’ve found that a good starting point while designing an API is to think about how myself or other engineers may want to use said API, this is also a good time to consider the limitations of our platform/system. It’s also a good idea to define some boundaries and/or non-functional concerns for our code:

- Python code should be able to determine the transaction’s inputs and outputs.

- Rust shouldn’t handle IO.

- We should be able to serialize the PSBT as

bytes. - We need to be able to estimate the transaction vsize since we’ll use it to estimate the miner’s fee.

With that in mind, we can scribble some Python code that utilizes our soon-to-be PsbtBuilder abstraction:

from btc import PsbtBuilder

AMOUNT_TO_CHARGE_SATS = 1000

def make_payment_psbt(user_utxo: Utxo, payment_address: str, miner_fee: int) -> bytes:

total_charge = miner_fee + AMOUNT_TO_CHARGE_SATS

assert user_utxo.value >= total_charge

builder = PsbtBuilder()

builder.add_input(user_utxo)

builder.add_output(our_address, AMOUNT_TO_CHARGE_SATS)

change_amount = user_utxo.value - total_charge

if change_amount > 0: # realistically, we may want to verify that the amount is greater than the dust value

builder.add_output(payment_address, change_amount)

return builder.serialize()

As you may have noticed, we’ll use the builder pattern to

incrementally build our PSBT by adding inputs and outputs, we also need a way to estimate the miner fee based on the

user provided fee rate in sats/vByte. Let’s start implementing our abstraction by declaring our PsbtBuilder struct

that we’ll expose as a Python class:

struct PsbtBuilderIn {

prevout: InputUtxo,

owner_address: Address,

owner_pub_key: Option<PublicKey>,

}

#[pyclass]

pub struct PsbtBuilder {

network: Network,

inputs: Vec<PsbtBuilderIn>,

outputs: Vec<TxOut>,

}

We are using the pyclass macro to generate the required boilerplate to register our struct as a Python class, we

also implemented a PsbtBuilderIn struct that we’ll use internally. There needs to be a way to instantiate and

initialize our new struct/PyClass, let’s declare a simple constructor function/method with PyO3’s #[new]:

#[pymethods]

impl PsbtBuilder {

#[new]

pub fn new(network: &str) -> PyResult<Self> {

let network =

Network::from_str(network).map_err(|e| PyValueError::new_err(e.to_string()))?;

Ok(Self {

network,

inputs: Vec::with_capacity(5),

outputs: Vec::with_capacity(5),

})

}

// other methods

}

#[pymethods] makes PyO3 expose the methods inside the impl block as methods of our PyClass, #[new] indicates which

method will be executed when our PyClass is instantiated. Let’s see how add_input is implemented:

#[pymethods]

impl PsbtBuilder {

// other methods

/// Add a new input to the PSBT, owner_pub_key is required for p2sh addresses

fn add_input(

&mut self,

utxo: InputUtxo,

owner_address: &str,

owner_pub_key: Option<&PyBytes>,

) -> PyResult<()> {

let owner_address = address_from_str(self.network, owner_address)?;

let owner_pub_key = owner_pub_key

.map(|pk| PublicKey::from_slice(pk.as_bytes()))

.transpose()

.map_err(|_| PyValueError::new_err("invalid public key"))?;

self.inputs.push(PsbtBuilderIn {

prevout: utxo,

owner_address,

owner_pub_key,

});

Ok(())

}

// other methods

}

Two interesting things are happening in add_input:

- The method receives an instance of a class declared in Python, this is possible because

InputUtxoimplements theFromPyObjecttrait. - The

owner_pub_keyargument is optional, we are able to achieve this by declaring it asOption<&PyBytes>. If we omit it when we call the method in Python, Rust will receive theNonevariant of theOption<T>enum.

Now it’s a good time to review how InputUtxo is implemented:

pub struct InputUtxo {

pub tx_id: Txid,

pub vout: u32,

pub (crate) value: Amount

}

impl FromPyObject<'_> for InputUtxo {

fn extract(obj: &'_ pyo3::PyAny) -> PyResult<Self> {

let tx_id =

obj.getattr("tx_id")?

.extract()

.map(Txid::from_str)?

.map_err(|_| PyValueError::new_err("invalid tx hash"))?;

let value =

obj.getattr("value")?

.extract()

.map(Amount::from_sat)?;

let vout = obj.getattr("vout")?.extract()?;

Ok(Self{

tx_id,

vout,

value,

})

}

}

// other impl for InputUtxo

As mentioned before, implementing the FromPyObject object allows us to customize how a Python value will “translate”

to Rust. In this case we’re assuming the object we’ll receive has the following attributes tx_id, value, vout; we

obtain a reference to them with getattr and then we cast them to Rust types with extract() so we can parse and

validate them to build a InputUtxo.

In some instances we may want to implement a method that we don’t want Python to be aware of or just use types that

can’t be converted to/from Python; when this is the case, we can have them in a different impl block without

#[pymethods], like we did for build:

impl PsbtBuilder {

fn build(&self) -> PyResult<psbt::Psbt> {

// code omitted for brevity

}

}

In this context psbt::Psbt is a type from the bitcoin crate that can’t be converted to a Python equivalent,

therefore we can’t expose this method to Python, so we’ll keep it in a separate impl block making it accessible to

Rust only. If you want to check the whole build method you can read it

here.

Now that our PyClass struct is ready, we just need to make sure to register it in our module. We can do so by calling

the add_class method of the PyModule struct in our btc function:

/// A Bitcoin helper module implemented in Rust

#[pymodule]

fn btc(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_class::<psbt::PsbtBuilder>()?;

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(get_address_type, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}

You can see the final version of the btc/src/lib.rs file

here. Unfortunately the module is too complex to test

it in the REPL, if you want to see a fully functional instance of the module working, you can run the provided sample

application. Follow the instructions in the repository’s README.

Type hints for our native class

Python’s type hints has been a welcomed addition to the language, unfortunately PyO3 doesn’t support the generation of

type hints at the time of writing, but we can add them manually by creating a btc/python/btc/__init__.pyi file:

class PsbtBuilder:

def __init__(self, network: str) -> None: ...

def add_output(self, address: str, amount: int) -> bool: ...

def add_input(

self, utxo: object, owner_address: str, owner_pub_key: bytes | None = None

) -> bool: ...

def estimate_vbytes(self) -> int: ...

def serialize(self) -> bytes: ...

def get_address_type(address: str) -> str: ...

Autocomplete and type checking should now work in editors that have support for them.

Conclusion

PyO3 makes a great effort to shorten the bridge between Python’s flexibility and ease of development and Rust’s performance and safety. Thanks to its many abstractions we’re able to write different parts of our application in Rust and interop with Python almost seamlessly, making it a great tool for our belt.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jessica for the cover image and Norman for the input during the early stages of this blog post.

Unspent Transaction Output ↩︎